More difficult than defining death can be coming to terms with it when others die and when we anticipate our own.

Death is an important subject or theme in art.

All cultures develop attitudes toward and activities involving death, some of which become traditions, often involving imagery, artifacts.

In ancient Egypt, beliefs concerning death and the afterlife resulted in complex rituals involving signs and symbols, ceremonial preparation of the body for burial, creation of elaborate burial architecture, furnishings, sarcophagi, etc.

As in Egypt, traditonal burial practises sometimes include the facture and placement of artifacts were placed to accompany the body in the burial or tomb, often to provide assistance to the soul of the deceased in the afterlife.

There is tremendous mystery to death, human cultures have generated myriad systems of belief to explain it, and to moderate the concerns the living may have about it.

Issues we associate with death:

Although proposperity, hygiene, science and technologies have been able to extend human lifespans, death bides its time.

Symbols of death: skulls and bones.

Art having something to do with death:

Egypt, Western Thebes, Section from the "Book of the Dead" of Nany, c. 1040-945 BCE, Dynasty 21, reigns of Psensennes I-II, Third Intermediate period, painted and inscribed papyrus, height of illustrated section 13 3/4 inches (34.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. See Egyptian art.

China, Jade Costume Sewn with Gold Wire, Western Han dynasty (206 BCE - 25 CE), 180 x 125 cm, Henan Museum, China. Unearthed at Yongcheng, Henan. Jade suits were the burial clothes of emperors and high-ranking nobles of the Han dynasty. They were made by tying jade pieces together with gold or silver or copper wire, according to the nobile ranking of the dead. This example was the burial suit of King Liang of the royal family of the Western Han dynasty. It is made up of 2008 pieces of jade sewn together with gold wire. It is composed of the head cover, face cover, upper garment, sleeves, gloves, trousers and foot covers. See Chinese art and Han dynasty.

Egypt, second century CE (Roman Period), Portrait of a Boy, encaustic on wood, height 15 3/8 x 7 1/2 inches (39 x 19 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. See Egyptian art and Fayum portraits.

Bodrum, Turkey, The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, height 140 foot, square in plan, marble, profusely decorated with statues of mythology figures, warriors mounted on horseback, stone lions, thirty-six slim columns, nine per side. The roof, which comprised most of the final third of the height, was in the form of a stepped pyramid, on top of which was a sculpture of four massive horses pulling a chariot occupied by the king and queen for whom the tomb was built — Mausolus and Artemisia.

Mausolus, with his queen, ruled over Halicarnassus from 377 BCE to his death in 353 BCE. Artemisia was so broken-hearted by her husband's death, she decided to build a great tomb for him. It became a structure so famous that its name became the word for a fine tomb. Artemisia spared no expense in the building this tomb. She involved the most talented artists of the period, chief among whom was Scopas, the man who oversaw the rebuilding of the Temple to Artemis at Ephesus. Such famous sculptors such as Bryaxis, Leochares and Timotheus joined him along with hundreds of other craftsmen. Artemisa lived for only two years after the death of her husband. Both were buried in the unfinished tomb, but craftsmen finished the work after their patron died "considering that it was at once a memorial of their own fame and of the sculptor's art," as Pliny put it. The Mausoleum remained largely intact until the first of several earthquakes brought it down in about the twelth century CE. By the fifteenth century only the very base of the ediface could be seen. In subsequent centuries, it was further plundered, and much of its marble recycled. The British Museum has several of its statues now in its "Mausoleum Room." See Wonders of the World.

Giunta Pisano (Italian, active in Pisa c. 1229-c. 1254), Crucifix, 1240s, tempera on wood, 316 x 285 cm, San Domenico, Bologna. Christ's act of submitting to suffering and death — crucifixion — is central to Christianity — to a belief in Jesus Christ as the savior of all of mankind from punishment for Adam and Eve's "original sin." Pisan was one of many artists who were influenced by an exposure to Byzantine art resulting from the capture of Constantinople by crusaders. Pisan's crucifix is noted for the extreme expression of pathos, inspired by the Eastern iconography of the 'Christus patient', that is the Brother of Man in His suffering. Under the influence of the Franciscans this interpretation was definitely substituted for the heroic Christ, impassive, triumphing over death.

Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, active by 1444, died 1475/76), The Lamentation, c. 1450, oil on wood panel, overall 10 1/8 x 14 inches (25.7 x 35.6 cm); painted surface 10 x 13 3/4 inches (25.4 x 34.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

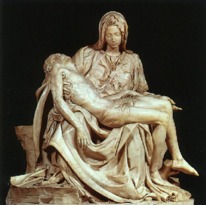

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564), The Rome Pietà [

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564), The Rome Pietà [detail of the faces of Christ and the Madonna], 1498-1500, marble, entire height 68 1/2 inches, maximum width of base 76 3/4 inches, maximum depth 27 1/8 inches, St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican, Rome. Carved in Rome for the French King Charles VIII's ambassador to Pope Alexander VI. See pietà and Renaissance.

Jan Polack (Polish, -1519), The Death of St. Corbinian, 1484-85, oil on wood panel, 147 x 129 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Northern Renaissance painter. See Polish art.

Hans Holbein The Younger (German, 1497/98-1543), Death and the Knight, 1538, woodcut, 65 x 50 mm, Spencer Museum, KS. Click here for a 101 k image.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder (Flemish, 1525/30-1569), The Triumph of Death, 1562, wood, (117 x 162 cm), Prado Museum, Madrid. See allegory.

France, Troyes, Dance of Death, 16th century, incunabulum, illustrated with hand-colored woodcuts, Saxon State Library, Dresden, Germany. Based on a fourteenth-century morality poem by an unidentifiable author, the Dance of Death evolved into a set of illustrated verses depicting a dialogue between Death and people of all social ranks. The theme was very popular in 15th and 16th century Christian Europe, reminding the living that rank and station in life were meaningless in the face of death. The illustrations show representations of ecclesiastical and secular society being carried off by Death. The pages displayed here show a pope, an emperor, a cardinal, and a king. See dance, illustration, and vanitas.

Artemisia Gentileschi (Italian, 1593-1651/53), Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1620, oil on canvas, 78 3/8 x 64 inches (199 x 162.5 cm), Uffizi, Florence. See Baroque, Caravaggisti and feminism and feminist art.

![]()

Pietro da Cortona (Italian, 1596-1669), Christ on the Cross with the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Saint John, about 1661, pen and brown ink, with gray-brown wash, heightened with white body color over black chalk, 15 7/8 x 10 7/16 inches (40.3 x 26.5 cm), J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, CA.

Nicolas Poussin (French, 1593/94-1665), The Death of Germanicus, 1627, oil on canvas, 58 x 77 3/8 inches, Minneapolis Institute of Arts. See Baroque and history painting.

Giuseppe Mazzuoli (Italian, c. 1644-1725), The Death of Adonis, 1709, marble, height 193 cm, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

John Singleton Copley (American and British, 1738-1815), The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781, 1783, oil on canvas, 251.5 x 365.8 cm, Tate Gallery, London. See flag.

Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825), The Death of Socrates, 1787, oil on canvas, 51 x 77 1/4 inches (129.5 x 196.2 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. (On the Met's page, you can enlarge any detail.) See Neoclassicism.

African American, Slave Pottery Jug, glazed ceramic in the form of a head, American Museum in Britain, Bath, whose curator says, "Slave pottery was known as Colono Ware. . . . It is possible that the face on this bottle represents Abraham Lincoln. Such jugs may have been made by slaves to protect the souls of the dead. They would have left them in graveyards." See early African American art.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, 1824-1904), Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), 1872, oil on canvas, 39.5 x 58.625 inches, Phoenix Art Museum. Gérôme studied the architecture of the Colosseum, along with other historical evidence in producing this history painting. To the right of the imperial throne, the vestal virgins indicate their desire for the death of a defeated combatant. Light streaming between sections of the canopy can be seen streaking across the floor and lower walls. Ridley Scott (American, contemporary) has said that this picture inspired his production of the movie Gladiator in 2000, starring Russell Crowe and Joaquin Phoenix. See Roman art.

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883), The Dead Christ and the Angels, 1864, oil on canvas, 70 5/8 x 59 inches (179.4 x 149.9 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906), Still Life with Skull (Nature morte au crane), 1895-1900, oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 5/8 inches (54.3 x 65 cm), Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania. Also see Post-Impressionism and vanitas.

Paul Cézanne, Pyramid of Skulls, c. 1901, oil on canvas, 14 5/8 x 17 7/8 inches (37 x 45.5 cm), private collection, Venturi no. 753.

Johann Mongles Culverhouse (American, active 1849-1891), Death of DeSoto, 1873, oil on canvas, New Britain Museum of Art, CT.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (English, 1836-1912), Death of the Pharoah's Firstborn Son, 1872, oil on canvas, 77 x 124.5 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. See Egyptian art, orientalism, and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Sir Luke Fildes (English, 1843-1927), The Doctor, 1891, oil on canvas, 166.4 x 241.9 cm, Tate Gallery, London. The Doctor was inspired by the memory of the death of the painter's son fourteen years earlier, and by the professional devotion of Dr. Gustavus Murray (1831-1887) who attended the child. Fildes gave his painting a happier ending. It shows the moment when, as dawn breaks, the patient shows the first sign of recovery.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848-1907), The Adams Memorial, 1890-1891, bronze (entire and a detail), Washington D.C., Rock Creek Cemetery. Also, a clay sketch (Dartmouth College Library).

Daniel Chester French (American, 1850-1931), The Angel of Death and the Sculptor from the Milmore Memorial, 1889-1893 (this version, 1926), marble, 93 1/2 x 100 1/2 x 32 1/2 inches (237.5 x 255.3 x 82.6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. The Milmore Memorial was commissioned by the family of the Boston sculptor Martin Milmore (1844-1883) to honor his memory and that of his brother, Joseph (1841-1886). See memorial.

James Ensor (Belgian, 1860-1949), Death Chasing the Flock of Mortals, 1896, drypoint and etching, plate: 9 7/16 x 7 3/16 inches (23.9 x 18.2 cm), Museum of Modern Art, NY. Ensor was a forerunner of Expressionism and Surrealism.

![]()

![]()

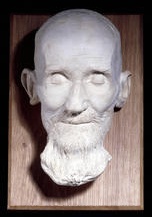

Charles Smith (English), Death mask of George Bernard Shaw, Irish-English playwright, 1856-1950, plaster, British Museum, London. See death mask and life mask.

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971), Jewish Prisoners at the Fence at Buchenwald, 1945, photograph. At the end of World War II, Margaret Bourke-White was with General Patton's Third Amy when they reached Buchenwald on the outskirts of Weimar. Patton was so incensed by what he saw that he ordered his police to get a thousand civilians to make them see with their own eyes what their leaders had done. The MPs were so enraged they brought back 2,000. Bourke-White said, "I saw and photographed the piles of naked, lifeless bodies, the human skeletons in furnaces, the living skeletons who would die the next day... and tattoed skin for lampshades. Using the camera was almost a relief. It interposed a slight barrier between myself and the horror in front of me." LIFE published in their May 7, 1945 issue many photographs of these atrocities, saying, "Dead men will have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them." See fascist aesthetic, Jewish art, and xenophobia.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954), El suicido de Dorothy Hale (The Suicide of Dorothy Hale), 1939, oil on Masonite panel with painted frame, Phoenix Art Museum, AZ. See feminism, Mexican art and self-portrait.

Luis Jiménez (American, 1940-2006), Southwestern Pietà, 1983,

30 x 44 inches, lithograph, collection of Gary D. Keller Cárdenas. The Hispanic Research Center at Arizona State University offers further information about Luis Jiménez, this artwork,

30 x 44 inches, lithograph, collection of Gary D. Keller Cárdenas. The Hispanic Research Center at Arizona State University offers further information about Luis Jiménez, this artwork, a large sculpture by Jiménez with the same title, and the contexts of these works, along with viewpoints for interpreting them. See Chicano/a art.

![]()

Zarco Guerrero (American, 1952-), Flower Calaca. This is a mask designed to celebrate the Mexican holiday Día de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead).

Maya Lin (American, 1959-), Vietnam War Memorial, Washington, D.C.,1982, a powerfully evocative minimalist monument, a V-shaped wall of polished black granite on which have been carved the names of Americans who died. The height of the wall is 10.1 feet at its center. The entire length of the wall is 493.5 feet; each half is 246.75 feet long. The wall contains 58,175 names (as of October 1990). The names (and other words) on the wall are 0.53 inches high and 0.015 inches deep. See chevron and memorial.

Also see cairn, catacombs, copyright, DWM, kiss of death, love, malanggan,[dead ends in] maze, mystery, necropolis, poison, posterity, posthumous, symbols, taxidermy, and vanitas.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()