The term, however, refers more to a style associated with Byzantium than to its area. Byzantine paintings and mosaics are characterized by a rich use of color and figures which seem flat and stiff. The figures also tend to appear to be floating, and to have large eyes. Backgrounds tend to be solidly golden or toned. Intended as religious lessons, they were presented clearly and simply in order to be easily learned. Early Byzantine art is often called "Early Christian art."

Byzantine architects favored the central plan covered by a huge dome.

Making generalizations about the visual culture of any group of people is a crude endeavor, especially with a culture as diverse as Byzantium's. With this thought in mind, know that this survey, as any must be, is tremendously limited in its breadth and depth.

(pr. bi"zn-teen')

Examples:

Byzantium, Constantinople, Fragment of a Sarcophagus, early 5th century, marble relief, height 142 cm, width 124 cm, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin. See fragment and sarcophagus.

Italy, Ravenna, Mosaic, c. 545/46, tesserae (cubes) of colored glass and stone, 432 x 615 cm, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin.

Byzantine (Constantinople or Sinai?), second

half of the 13th century, Icon with the Archangel Gabriel, tempera and gold on wood

panel with raised borders, 105

x 75 cm (41 3/8 x 29 1/2 inches), Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine,

Sinai, Egypt. One of the masterpieces

of Byzantine art,

this icon

shows the archangel Gabriel as a youth of extreme beauty. His graceful posture and harmonious

gestures, along with the

calmness of his face, are evocative of classical

art. The figure

wears a light green tunic and a himation

covered with golden highlights.

According to the eleventh-century writer Michael Psellos, a fillet

such as that around the curly hair signifies the purity, chastity,

and incorruptibility of the angels. Gabriel's function as a messenger

is indicated by the walking staff he holds in his left hand,

while he makes a gesture of adoration and supplication with his

right hand. This icon was part of a larger group, very

likely forming a deesis.

See angel.

Byzantium, Constantinople, Hagia Sophia, South Gallery or Catechumena, The Deesis, third quarter of the 13th century, mosaic, Istanbul, Turkey. Christ's left hand holds a closed Book of Gospels as he raises his right hand in benediction. His face is strikingly realistic and expressive, as are those of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist, who stand to either side of Christ. All are set against a golden background. The lower portion of the composition has been damaged. This and all other mosaics in Hagia Sophia were covered with plaster at the church's conversion into a mosque in the 15th century. This actually preserved the mosaics for later restoration, which began in 1929, when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk ordered the conversion of the mosque into a museum. See art conservation, deesis , detail, deesis, and lacuna.

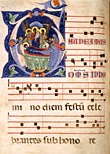

Gerona Bible Master, Bologna, Italy, Gradual,

Proper and Common of Saints (folio

84 verso in Manuscript

526), c. 1285, tempera on vellum, one of 290 folios,

51.5 x 35.5 cm (20 1/4 x 14 inches), Musei Civici d'Arte Antica,

Bologna. Black marks arranged on the horizontal

lines ("staff")

displayed here exemplify the system of musical

notation used in Italy during much of the Middle

Ages. The Latin text

(or lyric) opens with "Gaudeamus," meaning "Let

us rejoice." The initial letter "G" is historiated

in late Byzantine style. This "gradual"

is one of a set of three that together comprise the sung portions

of the Mass for the entire church year.

Byzantium, The Cambrai Madonna, c. 1340, Metropolitan

Museum of Art. About a hundred years after it was produced, Canon

Fursy de Bruille acquired this icon

in Rome. He was told that it was a holy relic:

it had been painted by St. Luke himself. In 1440, the canon gave

the painting to the Cathedral of Cambrai, France, where thousands

of pilgrims saw it. The image

shows Jesus squirming in his mother's arms. Mother and child,

doleful and shy, turn slightly toward us, as if they are watching

or waiting for something. The Cambrai Madonna conforms to a type,

"the Virgin of Tenderness," an invention of the late

Byzantine era. See Madonna.

Byzantine, 14th century, Reliquary Box

with Scenes from the Life of John the Baptist, tempera

and gold on

wood, 9 x 23.5 x 9.9 cm (3 5/8

x 9 1/4 x 4 inches), Cleveland Museum of Art, OH. Here are enlargements

of two views of this reliquary -- first and second. See Byzantine

art.

![]()

![]()

Byzantine, 14th century, Hexaptych Icon with Scenes from the Great Feasts

(obverse), Apostles, Saints, and Angels (reverse),

tempera and gold on six wood

panels, 31 x 13.5 cm (12 1/4 x

5 3/8 inches) each panel, Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine,

Sinai, Egypt. See polyptych.

Byzantium, Christ Pantocrator, 1363, egg

tempera on gesso, wood, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg,

Russia. This icon

was created for the Monastery of the Pantocrator on Mount Athos.

It is a characteristic work from the last high period of Constantinople

painting, the late 14th and early 15th centuries. See monastery.

Kach'atur, illustrator, and Yohannes, scribe (priests in Khizan,

Byzantine Greater Armenia), The Gospels, 1455, tempera

and black ink on paper,

27.5 x 18 cm (10 7/8 x 7 1/8 inches), Walters Art Museum, Baltimore,

MD. This Christian book was illuminated at a time when the Timurids — an Islamic sultanate — were in power in this region. Christian Constantinople

itself had been conquered in 1453. Although the iconography is within Christian traditions,

much of the patterning and costume here reflect the taste of

the Timurids. The dramatic gestures of the figures in the narrative, the background

details, the serpentine,

almost abstract line of the drapery folds,

the pattern of the wings, and Christ walking in pants with yellow

boots — all are more closely allied to the taste of the Islamic

world in which the Armenians of Khizan lived.

Also see taxis.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()