February is African American History Month! ![]()

![]()

African American art

African American art

By Richard J. Powell

Abstraction and Realism during the Postwar Years

This balancing act between a race consciousness in art and visual assimilation into the white cultural mainstream — exemplified most emphatically in a nonfigurative, abstract art — was undermined by several artists in the post-World War II years. The work of these artists — decidedly abstract and expressionistic yet at times referential to Africa, black America, and to the evolving civil rights struggle — necessitated an altogether different definition of what was then described as modern Negro art. At the forefront of this new paradigm was Hale Woodruff, whose integration of African-design motifs into his colorful, large-scale canvases stood alongside an enigmatic and symbol-laden painterly abstraction in works by other painters. Similarly, a 1950s brand of New York School abstraction was defined in part by the “all-over” compositions of painter Norman Lewis. Lewis, a master of visual wit, irony, and critique, figured in contradistinction to another abstractionist, Beauford Delaney, who wavered between completely nonillusionistic, gestural canvases and thickly painted, expressive portraits.

In the midst of this moment when abstract art was considered the status quo, several figurative artists, among them Hughie Lee-Smith and Charles White, achieved broad recognition. Lee-Smith painted desolate, urban landscapes inhabited by solitary people of different ages and sexes and across the racial spectrum. White, whose career dated back to the 1930s, produced in the 1950s a series of monumental crayon and ink drawings of idealized African American figures. These works, when thematically framed by the news reports of civil rights bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins, and attacks on black protesters by angry whites, took on an even greater power than their abstract counterparts in explicitly communicating something about African American aspirations and dreams. Minnie Evans and James Hampton, although far removed from the New York art scene in their respective communities of Wilmington, North Carolina, and Washington, DC, created powerful artistic statements during this period that not only reintroduced so called folk elements into the art world, but added a spiritual dimension to black visual culture as well.

The two 1960s artists whose careers and products may be considered to have formed a bridge between the visual past (the omnipresent black figure, overtures to visual modernism, and the need to acknowledge the politics of race) and a visual future for African American art (artistic singularity over racial unity, narrational/perceptual simultaneity, and the interjecting of class, gender, and sexuality into art) are Bob Thompson and Romare Bearden. The colorful, silhouetted, and enigmatic figures in Thompson’s paintings, derived from the works of the old masters of European painting and the new young lions of jazz, introduced a whole new set of options in African American visual culture. Similarly, the cut-up, collaged, and reconstituted images of Afro-America that Bearden introduced to the public in 1964 inaugurated an expanded and progressive view of art and art-making: a picture that reflected ambiguity, complexity, nuance, and affirmation in black culture.

Examples:

Selma Burke (American, 1901-1995)

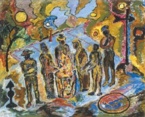

Beauford Delaney (American, 1902-1979), Can Fire in the Park, 1945?, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. This painting is one of many New York scenes the artist painted before emigrating to paris in 1953.

Beauford Delaney, Untitled, 1946, oil on canvas.

Norman Lewis (American, 1909-1979), Evening Rendezvous, 1962, oil, 50 1/4 x 64 1/4 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Romare Bearden (American, 1914-1988), The Family, 1948, watercolor and gouache on paper.

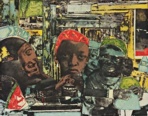

Romare Bearden, Patchwork Quilt, 1970, cut-and-pasted cloth and paper with synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 35 3/4 x 47 7/8 inches (90.9 x 121.6 cm), Museum of Modern Art, NY.

Romare Bearden, Empress of the Blues (Bessie Smith with Band), 1974, acrylic, pencil, and printed paper, 36 x 48 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Romare Bearden, The Train, 1975, photogravure and aquatint, plate: 17 11/16 x 22 1/8 inches (44.9 x 56.2 cm); sheet: 22 1/4 x 30 1/8 inches (56.5 x 76.5 cm); publisher: Transworld Art, NY; printer: Printmaking Workshop, NY; Museum of Modern Art, NY.

Romare Bearden, The Return of Odysseus, 1977, collage on Masonite. The Return of Odysseus portrays the climax of The Odyssey, an epic poem by the ancient Greek author known as Homer.

Visit the Romare Bearden Foundation and "Let's Walk the Block," about Romare Bearden's 6-panel 1971 collage, The Block at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

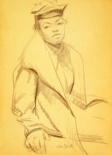

Hughie Lee-Smith (American, 1915-2000), Untitled, c. 1930, pencil on paper, 12 x 8 inches, Butler Institute of American Art, OH.

Hughie Lee-Smith, Reflection, 1957, oil on canvas.

Charles Wilbert White (American, 1918-1979), The Return of the Soldier, 1946, pen and ink on paper, Heritage Gallery, Los Angeles.

Charles Wilbert White, Untitled, 1970, lithograph (stone) in brown on uncalendered Rives paper, sheet: 63.6 x 94 cm (24 x 37 inches), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC . See social realism.

Charles White, Sounds of Silence, 1978, lithograph on paper.

Faith Ringgold (American, 1930-), The Flag is Bleeding #2, acrylic on canvas; painted and pieced border, 76 x 79.5 inches, from the series "The American Collection," #6. See feminism and feminist art and flag. Visit the artist's Web site.

Bob Thompson (American, 1937-1966), Music Lesson, 1962, oil on canvas. See Fauvism, music, and Neoclassicism.

Bob Thompson, Homage to Nina Simone, 1965, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Norman Lewis (American, 1909-1979), Evening Rendezvous, 1962, oil, 50 1/4 x 64 1/4 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

This is part 6 of ArtPage on African American art

_____

The author of this article, Richard J. Powell PhD, is a professor of art and art history at Duke University who specializes in American, African American and African art. His books include Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997), and Black Art: A Cultural History (2002).

Copyright © 2005 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, second edition. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Thanks to Yolanda Carden for permission to post this excerpt in ArtPage.

Oxford University Press; April 2005; 5 Volumes; 4,500 pp.; 0-19-517055-5; Special introductory price until April 30th, 2005 of US $425.00. After April 30th, 2005, the price will be US $500.00. Please visit the Oxford University Press for ordering information.

Ninety years after W.E.B. Du Bois first articulated the need for “the equivalent of a black Encyclopedia Britannica,” Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr., realized his vision by publishing Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience in 1999. This new multi-volume edition of the original work expands on the foundation provided by Africana. More than 4,000 articles cover prominent individuals, events, trends, places, political movements, art forms, business and trade, religion, ethnic groups, organizations and countries on both sides of the Atlantic.

![]() About the Editors:

About the Editors:

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. is W. E. B. Du Bois Professor of Humanities, Chair of the Department of African and African American Studies, and Director of the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Harvard University. Professor Gates is well known as an innovator in the field of African American studies and as the author of numerous works.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is the Lawrence S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Also see African art, Afrocentrism, bias, discrimination, ethnic, ethnocentrism, multiculturalism, xenophilia, and xenophobia.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()