February is African American History Month! ![]()

![]()

African American art

African American art

By Richard J. Powell

The Harlem Renaissance

The social and political anxieties that many African Americans felt just after World War I (1914-1918) were alleviated, in part, by mass migrations to the urban North. Northern cities offered a respite from the repressive attitudes and mandates of the old Southern order. The new racial compositions of cities like Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, and Saint Louis, in combination with a heightened social consciousness and a seemingly unbound desire for leisure and escapism, conspired to help create the cultural phenomenon known as the New Negro movement. Part social engineering and part spontaneous expression, this Harlem Renaissance (as the cultural movement later became known) was realized by a mix of American movers and shakers: social reformers, political activists, cultural elites, progressives in public policy and education, and, of course, artists. Although each of these constituencies had its own reasons for promoting African American achievements in the literary, musical, visual, and performing arts, the collective results of these endeavors was an unprecedented, broad-based focus on African Americans, their art, and the connections to a larger, modernist vision.

Visual artists played a key role in creating depictions of the New Negro. Alongside their counterparts in literature, music, and theater, painters Palmer C. Hayden, Malvin Gray Johnson, and Laura Wheeler Waring, among others, exhibited bold, stylized portraits of African Americans during this period, as well as scenes of black life from a variety of perspectives. Sculptors Richmond Barthé, Sargent Johnson, and Augusta Savage used clay, wood, and bronze to create comparable representations.

Book and magazine publishers of the 1920s and 1930s also helped to disseminate Harlem Renaissance imagery. Published in the pages of The Crisis, Opportunity, and New Masses were the blockprint illustrations of James Lesesne Wells, the etchings and drawings of Albert Alexander Smith, and the illustrations and jacket covers of one of the period’s most prolific artists, Aaron Douglas.

Examples:

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983), Evening Attire,

1922,

gelatin silver print,

10 x 8 inches,

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983), Alpha Phi Alpha Basketball Team, 1926, photograph.

Sargent Claude Johnson (American, 1887-1967), Mask,

about 1930-35, copper on wood base,

15 1/2 x 13 1/2 x 6 inches,

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. See mask.

Sargent Claude Johnson, Singing Saints, 1940, lithograph on paper. See stylize.

Laura Wheeler Waring (American, 1887-), Still Life, 1929, oil on canvas. See still life.

Palmer Hayden (American, 1890-1973), Nous Quatre a Paris (We Four in Paris), no date, watercolor on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Palmer Hayden, The Janitor Who Paints,

about 1937, oil,

39 1/8 x 32 7/8 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Palmer Hayden, Jeunesse, no date, watercolor on paper, 14 x 17 inches, collection of Dr. Meredith F. Sirmans, NY. This and works by many other artists the Harlem Renaissance were influenced by their enjoyment of jazz, an often improvisational musical form developed during the 1920s by African Americans and influenced by European harmonic structure and African rhythmic complexity. Jazz can be identified by its characteristic blues rhythms and distinctive speech intonations. Harlem has long been an important center for jazz. Palmer Hayden could have seen such dancing as this at the Savoy, which was Harlem's most famous jazz club.

Archibald J. Motley (American, 1891-1981), Mending Socks, 1924, oil on canvas, Ackland Art Museum, U of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

![]()

Archibald J. Motley, Blues, 1929, oil on canvas.

Archibald J. Motley, Nightlife, 1943, oil on canvas, 91.4 x 121.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, IL.

Archibald Motley Jr., After Fiesta, Remorse, Siesta, 1959-1960, oil on canvas.

![]()

Augusta Savage (American, 1892-1962), Gamin, 1930, bronze. See bust.

Malvin Gray Johnson (American, 1896-1934), Brothers, 1934, oil,

38 x 30 1/8 inches,

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

![]()

Aaron Douglas (American, 1898-1979), Sahdji, c. 1925, ink and graphite on wove paper, 12 1/16 x 9 inches.

Aaron Douglas, Crucifixion, 1927, oil on canvas.

![]()

Aaron Douglas, Rebirth, 1927, oil on canvas.

Aaron Douglas, Study for Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting, 1934, gouache on Whatman artist’s board, 37.1 x 40.6 inches, Art Institute of Chicago, IL. Aaron Douglas's paintings show that he was particularly influenced by ancient Egyptian sculpture and the modern Art Deco style.

Aaron Douglas, Aspects of Negro Life #62: Song of the Towers, 1934, oil on canvas.

Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, 1936, oil on canvas, 60 3/8 x 60 1/2 inches (153.35 x 153.67 cm), Corcoran Gallery, Washington, DC.

Hale Woodruff (American, 1900-1980), Landscape, 1936, oil on canvas.

![]()

Hale Woodruff, Caprice, 1962, oil on canvas.

Richmond Barthé (American, 1901-1989), Portrait of Harold Jackman, 1929, charcoal and pastel on paper.

Richmond Barthé, Blackberry Woman, 1932, bronze, 33 3/4 x 11 x 14 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Richmond Barthé, Feral Benga (Benga: Dance Figure), 1935, bronze, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX.

James Lescesne Wells (American, 1902-1992), Escape of the Spies from Canaan, about 1933, linoleum cut print.

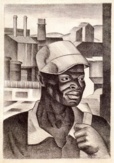

James Lescesne Wells, Negro Worker, about 1938 orginal, lithograph on paper.

This is part 4 of ArtPage on African American art

_____

The author of this article, Richard J. Powell PhD, is a professor of art and art history at Duke University who specializes in American, African American and African art. His books include Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997), and Black Art: A Cultural History (2002).

Copyright © 2005 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, second edition. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Thanks to Yolanda Carden for permission to post this excerpt in ArtPage.

Oxford University Press; April 2005; 5 Volumes; 4,500 pp.; 0-19-517055-5; Special introductory price until April 30th, 2005 of US $425.00. After April 30th, 2005, the price will be US $500.00. Please visit the Oxford University Press for ordering information.

Ninety years after W.E.B. Du Bois first articulated the need for “the equivalent of a black Encyclopedia Britannica,” Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr., realized his vision by publishing Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience in 1999. This new multi-volume edition of the original work expands on the foundation provided by Africana. More than 4,000 articles cover prominent individuals, events, trends, places, political movements, art forms, business and trade, religion, ethnic groups, organizations and countries on both sides of the Atlantic.

![]() About the Editors:

About the Editors:

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. is W. E. B. Du Bois Professor of Humanities, Chair of the Department of African and African American Studies, and Director of the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Harvard University. Professor Gates is well known as an innovator in the field of African American studies and as the author of numerous works.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is the Lawrence S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Also see African art, Afrocentrism, bias, discrimination, ethnic, ethnocentrism, multiculturalism, xenophilia, and xenophobia.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()