February is African American History Month! ![]()

![]()

African American art

African American art

By Richard J. Powell

Civil War and Post-Reconstruction Years

The tensions between an art that referred to people’s social conditions and an art that transcended race and class politics are represented by the works of two artists active during the 1860s and 1870s: sculptor Edmonia Lewis and landscape painter Robert Scott Duncanson. Lewis -- who studied art at Oberlin College, independently in Boston, Massachusetts, and among American and British expatriates in Italy -- used the artistic conventions of neoclassicism to create powerful marble statuary on the subjects of black American emancipation, female oppression, and Native Americans. Duncanson -- working mostly in Cincinnati, Ohio, and other locations in the Ohio River Valley -- painted dreamy, pastoral scenes that recalled the aesthetics of the Hudson River school rather than overtly racial and political themes. Yet the racially tinged ordeals that both of these artists grappled with at various points in their careers gave even their most apolitical portrait busts and landscape allegories a social dimension, thus justifying the African American designation of their work.

A similar political/apolitical bifurcation is present in the work and lives of artists working between 1865 and 1900. First against a social backdrop of enfranchisement and hope and later against one of disenfranchisement and despair, landscape painters like Edward Mitchell Bannister and William Harper created moody, Barbizon School-like scenes, bereft of the political jockeying and white-on-black violence that characterized African American lives at the end of the century. For painter Henry Ossawa Tanner the pressures of American racism and the burdens of representing his race were too great. His 1891 move to Paris, France, encouraged his interest in painting mostly biblical scenes in a part academic, part symbolist manner. In contrast, the Athens, Georgia, seamstress Harriet Powers, oblivious to the world of art galleries and exhibitions, created at least two powerful Bible quilts that bore strong similarities to West African textile arts, especially to the cloth appliqués from the Akan and Fon peoples.

Increasingly, heroic and uplifting portrayals of African Americans appeared in paintings and sculpture in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Artist Edwin A. Harleston was renowned for his paintings of distinguished (and affluent) black Americans. Sculptors Isaac Scott Hathaway and May Howard Jackson also dedicated much of their careers to creating portrait busts of African American notables past and present. In the pages of the journal The Voice of the Negro artist John Henry Adams, Jr., created dozens of African American portraits: finely drawn and idealized in the manner of the white illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, but informed by an emerging racial consciousness. In the more symbolic and allegorical works of the sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller, a black cultural cognizance manifested itself in important nineteenth-century topics such as emancipation and in pieces that foreshadowed several themes that would be important for artists and intellectuals in subsequent years (the African past, a black cultural rebirth, etc.).

Examples:

Edmonia Lewis (American, c. 1845 - 1911), Old Arrow Maker, modeled 1866, carved 1872, marble, 21 1/2 x 13 5/8 x 13 3/8 inches (54.5 x cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, marble,

41 1/4 x 22 x 17 inches, Howard University, Washington, DC.

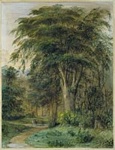

Robert Scott Duncanson (American, 1821-1872), Mount Royal, 1864, watercolor on wove paper,

95.3 x 71.9 cm, National Gallery of Canada. See Hudson River School.

Robert Scott Duncanson, "The Water Nymphs (The Surprise)," 1868, oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 66 1/2 inches, Howard University, Washington, DC.

Robert Scott Duncanson, A Wet Morning on the Chaudière Falls, 1868, oil on canvas, 76.6 x 111.7 cm, National Gallery of Canada.

Edward Mitchell Bannister (American, 1828-1901), Landscape with a Boat, 1898, oil on canvas.

Louis Schultze (American, ), Portrait of Dred Scott, 1882, commissioned by "a group of Negro citizens," painted after the only known photograph of Scott, and presented to the Missouri Historical Society in 1882, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

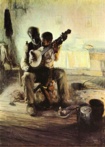

Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859-1937), The Banjo Lesson, 1893, 49 x 35 1/2 inches, oil on canvas, Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia. Tanner studied under the realist painter Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the 1880s. There he endured abuse from his white colleagues, and continually struggled with his identity as an African-American artist. Tanner only gained recognition in the USA after he settled in Paris in 1894.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Two Disciples at the Tomb, c. 1905, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 105.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.

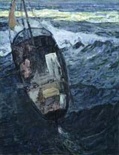

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Fishermen at Sea,

about 1913, oil,

46 x 35 1/4 inches,

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Street Scene, Tangiers, 1913, etching on paper.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, about 1918, oil on artist board.

William Harper (American, 1873-1910), Patio, 1908, oil on canvas.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (American, 1877-1968), Ethiopia Awakening, 1914, bronze, New York Public Library. Drawing on Egyptian sculptures and themes, this statue recalls the African heritage of black Americans. Larger image of the second photo.

This is part 3 of ArtPage on African American art

_____

The author of this article, Richard J. Powell PhD, is a professor of art and art history at Duke University who specializes in American, African American and African art. His books include Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997), and Black Art: A Cultural History (2002).

Copyright © 2005 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, second edition. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Thanks to Yolanda Carden for permission to post this excerpt in ArtPage.

Oxford University Press; April 2005; 5 Volumes; 4,500 pp.; 0-19-517055-5; Special introductory price until April 30th, 2005 of US $425.00. After April 30th, 2005, the price will be US $500.00. Please visit the Oxford University Press for ordering information.

Ninety years after W.E.B. Du Bois first articulated the need for “the equivalent of a black Encyclopedia Britannica,” Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr., realized his vision by publishing Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience in 1999. This new multi-volume edition of the original work expands on the foundation provided by Africana. More than 4,000 articles cover prominent individuals, events, trends, places, political movements, art forms, business and trade, religion, ethnic groups, organizations and countries on both sides of the Atlantic.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is the Lawrence S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Also see African art, Afrocentrism, bias, discrimination, ethnic, ethnocentrism, multiculturalism, xenophilia, and xenophobia.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()