February is African American History Month! ![]()

![]()

African American art

African American art

By Richard J. Powell

African American Art and Postmodernism

By the mid- to late 1980s earlier definitions of African American art would be supplanted by the postmodernist tenets of cultural relativity, art-as-performance, critical inquiries of art and society through one’s work, and interrogations of identity, geography, and history. Several artistic precursors to this new generation had already begun to exhibit these more provocative, postmodernist characteristics in their work. For example, by 1975 artist David Hammons was already creating sculptures from black cultural detritus (hair, food, artifacts, etc.) that ironically commented on black identity. Around the same time Robert Colescott was making outlandish, cartoon-like paintings that poked fun at the art establishment, cultural conservatives, and ethnocentrism. In contrast, conceptual artist Adrian Piper countered the reigning avant-garde of her day with performances that placed racism at the center of art matters. Also at this time artist Houston Conwill wrestled with the notion of African American space, initially through site-specific earthworks and, later, through culturally informed diagrams and signs.

These pioneers of an African American visual postmodernism helped put into motion a different set of visual criteria in contemporary art: models that, in turn, have engendered an innovative group of artists. This inventive group includes sculptors Alison Saar and Renée Stout and photographers Albert Chong and Lyle Ashton Harris, who explore concepts of objecthood and fetishism; visual artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Glenn Ligon, and Lorna Simpson, for whom issues of gender and language are central in art; photographers Dawoud Bey, Renee Cox, and Lorraine O’Grady and painters Kerry James Marshall and Howardena Pindell, each of whom presents the black body as a site of theoretical warfare, social research, and desire; and conceptualists like Gary Simmons, Kara Walker, and Fred Wilson who, through installation art, have problematized American history and the psychology of racism so that display and spectatorship can no longer be viewed as purely innocent acts.

Examples:

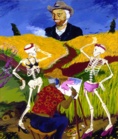

Robert Colescott (American, 1925-), Auvers-sur-Oise (Crow in the Wheat Field), 1981, acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 inches, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

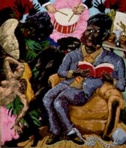

Robert Colescott, Feeling His Oats, 1988, acrylic on canvas, 90 x 114 inches, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

Robert Colescott, Marching to a Different Drummer, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 inches (213.4 x 182.9 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Martin Puryear (American, 1941-), Vault, 1984, wood, wire mesh, and tar, 66 x 97 x 48 inches, Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, CA.

Martin Puryear, Lever No. 3, 1989, carved and painted wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

David Hammons (American, 1943-), Untitled, 1989, glass wine bottles and silicon glue, 37 1/4 x 37 1/2 x 7 3/4 inches (84.6 x 95.1 x 19.5 cm), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC.

Howard Pindell (American, 1943-), Untitled, c. 1977, mixed media on matboard.

Carrie Mae Weems (American, 1953-), From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995, a series of chromogenic photographic color prints with sand-blasted text on glass, of which this is one, 42 x 31 inches, Museum of Modern Art, NY. The artist selected nineteenth- and twentieth- century photographs of black men and women, from the time they were forced into slavery in the United States to the present, then rephotographed the pictures, enlarged them, and toned them in red. Each photograph is framed under a sheet of glass inscribed with a text written by the artist, evoking the layers of prejudice imposed on the depicted men and women. See feminist art and xenophobia.

Alison Saar (American, 1956-), Subway Preacher, 1984, tin, wood, canvas, mixed media, 89 x 56 x 31 inches (226.0 x 142.2 x 78.7 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

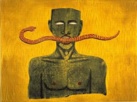

Alison Saar, Snake Man, 1994,

color woodcut and lithograph,

28 x 37 1/4 inches, Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Alison Saar, Lave Tête (Washing of Head), 2001, mixed media, Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, OH.

Renée Stout (American, 1958-), Ogun, 1995, mixed media, Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, NC.

Lorna Simpson (American, 1960-), 2 Frames, 1990, photograph, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, TX.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (American, 1960-1988), Untitled (Skull), 1981, acrylic and mixed media on canvas,

81 x 69 1/4 inches, Broad Art Foundation.

Glenn Ligon (American, 1960-), Untitled: Four Etchings, 1992, four softground etching, aquatint, spit bite and sugarlifts on paper, 25 x 17 1/4 inches each, Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica, CA. See text.

Glenn Ligon, Stranger in the Village #13, 1998, enamel, oil, synthetic polymer, gesso, and coal dust on canvas, 182.9 x 335.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.

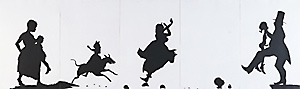

Kara Walker (American, 1969-), A Means to an End A Shadow Drama in Five Acts, 1995, hard-ground etching and aquatint on five sheets, Landfall Press Archive, Milwaukee Art Museum, WI. See projection and silhouette.

Kara Walker, Danse de la Nubienne Nouveaux, 1998, paper silhouette installation, 120 x 240 inches overall, Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica, CA.

This is part 8 of ArtPage on African American art

_____

The author of this article, Richard J. Powell PhD, is a professor of art and art history at Duke University who specializes in American, African American and African art. His books include Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997), and Black Art: A Cultural History (2002).

Copyright © 2005 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, second edition. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Thanks to Yolanda Carden for permission to post this excerpt in ArtPage.

Oxford University Press; April 2005; 5 Volumes; 4,500 pp.; 0-19-517055-5; Special introductory price until April 30th, 2005 of US $425.00. After April 30th, 2005, the price will be US $500.00. Please visit the Oxford University Press for ordering information.

Ninety years after W.E.B. Du Bois first articulated the need for “the equivalent of a black Encyclopedia Britannica,” Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr., realized his vision by publishing Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience in 1999. This new multi-volume edition of the original work expands on the foundation provided by Africana. More than 4,000 articles cover prominent individuals, events, trends, places, political movements, art forms, business and trade, religion, ethnic groups, organizations and countries on both sides of the Atlantic.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is the Lawrence S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

Also see African art, Afrocentrism, bias, discrimination, ethnic, ethnocentrism, multiculturalism, xenophilia, and xenophobia.

https://inform.quest/_art

Copyright © 1996-![]()